Sign up now for a weekly digest of the top drug and alcohol news that impacts your work, life and community.

After receiving a number of calls from parents of young adults who are addicted to drugs, asking whether they can force their child into treatment against their will, the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NASMDL) found it is possible to do so in 37 states—if strict guidelines are met.

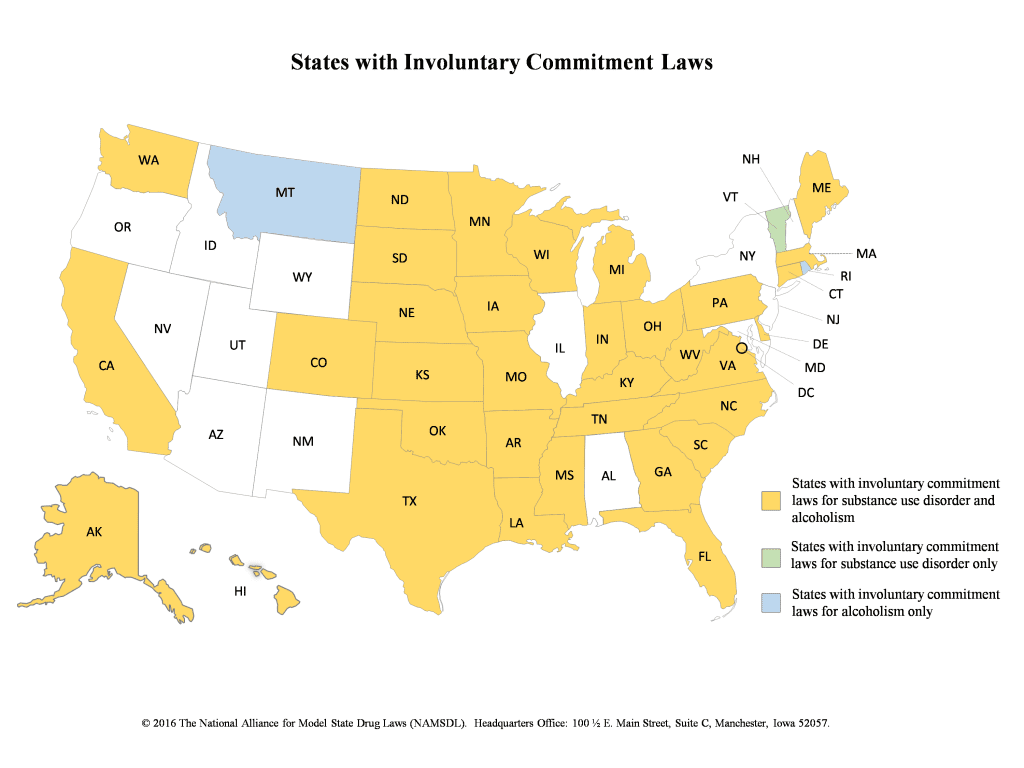

According to Heather Gray, NAMSDL Senior Legislative Attorney, 37 states and the District of Columbia currently have statutes in place allowing for the involuntary commitment of individuals suffering from substance use disorder, alcoholism, or both.

The bar for proving the need for involuntary commitment is high, Gray notes, adding, “Parents of minors can drive their child to a treatment facility against their will, but once the child turns 18, there’s a lot less they can do.”

In order for a person to be involuntarily committed for addiction treatment, it first has to be proven the person is addicted to drugs or alcohol. Typically, there must also be evidence that the individual has threatened, attempted, or inflicted physical harm on himself or another person, or proof that if the person is not detained, he will inflict physical harm on himself or another person. Or the person must be so incapacitated by drugs or alcohol that he cannot provide for his basic needs, including food, shelter, and clothing, and there is no suitable adult (such as a family member or friend) willing to provide for such needs.

Even if parents are able to get their child involuntarily committed, the severe lack of addiction treatment facilities in many areas means that there is often nowhere to send someone, Gray noted. “If more people knew involuntary commitment was an option, they might put pressure on legislators in their state to make more treatment facilities available, especially given the current climate with [the] opioid epidemic,” she says. “Many people need treatment and aren’t getting it because space isn’t available.”

The majority of states with involuntary commitment laws for substance use disorders and alcoholism specifically exclude substance use disorders and alcoholism from their legal definition of mental illness or mental disorder. This is likely due to criminal court considerations, with legislators not wanting criminal defendants who committed a crime while under the influence to be able to plead an insanity defense, according to Gray.

In every state with an involuntary commitment law, people sought to be committed have the right to an attorney or, if they cannot afford an attorney, to have the court or other committing agency appoint an attorney to represent them at every stage of the proceedings. Every state also grants people the right to petition for a writ of habeas corpus at any point after they have been committed. The purpose of a writ of habeas corpus is to have the court determine whether the person’s detention is lawful and, if not, to order the release of the individual.

While many state laws covering involuntary commitment are similar, there are variations in how long a person can be detained before having a hearing, from 48 hours to five days, she noted. In Louisiana, a person can be detained for 15 days before a hearing.

In many states, a person who is involuntarily committed for inpatient treatment is treated for about two weeks. After that, if the facility administrator or the patient’s doctor feels they are sufficiently able to care for themselves outside of the facility, they can be released to outpatient treatment. If they do not comply with outpatient treatment, they can be readmitted to the inpatient facility.

“It used to be that if you were committed involuntarily to an institution, you might be there for a year. Because that violated due process rights, a lot of state laws were modified in the 1960s and 70s so people could not be held for that long,” Gray says. “People have the right to live their lives as they choose, so there has to be a compelling reason to commit them involuntarily.”