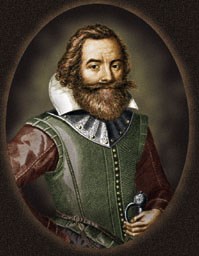

the Simon van de Passe engraving of Captain John Smith on his 1616 Map of New England." width="" />

the Simon van de Passe engraving of Captain John Smith on his 1616 Map of New England." width="" /> the Simon van de Passe engraving of Captain John Smith on his 1616 Map of New England." width="" />

the Simon van de Passe engraving of Captain John Smith on his 1616 Map of New England." width="" />

Captain John Smith was an adventurer, soldier, explorer and author. Through the telling of his early life, we can trace the developments of a man who became a dominate force in the eventual success of Jamestown and the establishment of its legacy as the first permanent English settlement in North America.

John Smith was baptized on January 9, 1580, at Saint Helena's Church in Willoughby, Lincolnshire, England. His parents were George and Alice Smith. George was a yeoman farmer who owned land in Lincolnshire and also rented land from Lord Willoughby, his landlord and relation by marriage.

As a young boy, John attended local grammar schools learning reading, writing, arithmetic, and Latin. Not wanting to be a farmer, John ran away at age 13 to become a sailor, but his father stopped him, making John work as an apprentice [a person who works for another in order to learn that trade] to a nearby merchant. In 1596, following the death of his father, John sailed for France and joined English soldiers fighting the Spanish there and in the Netherlands. A truce ended this fighting in 1598, and John returned to England a trained soldier.

Following another trip to France and to Scotland, Smith secluded himself in a wooded pasture on Lord Willoughby's property. Living in a shelter he built of tree branches, John learned how to live off the land, and he read books about the rules of war and politics. Lord Willoughby had an Italian nobleman, Signore Theodore Paleologue, visit Smith who helped him to improve his horsemanship and jousting skills. These lessons prepared Smith for his next adventure.

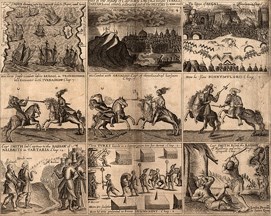

In 1600, learning of the war being fought between Christian forces of the Holy Roman Empire [HRE] and the Muslim Ottoman Turks, Smith set off for Austria to join the HRE army. On his way to Austria, Smith experienced several adventures, including serving on a pirate ship in the Mediterranean Sea. His pirate service earned him 500 gold pieces enabling him to complete his trip through Italy, Croatia and Slovenia to Austria where he joined the HRE army.

Smith fought against the Turks in battles waged in Slovenia, Hungary and Transylvania [Romania] earning several awards for his bravery in battle. One award was his promotion to captain, a title Smith remained proud of the rest of his life. The Prince of Transylvania gave Smith the title of "English gentleman", and with it a coat of arms that consisted of three Turks' heads representing the three Turks killed and beheaded by Smith in individual jousting duels. Smith had become a very accomplished soldier and leader. But his good fortune ended in 1602 when he was wounded and captured in battle and sold into Turkish slavery. Smith was forced to march 600 miles to Constantinople where a new adventure awaited the captain.

In Constantinople, the enslaved Smith was presented by his master as a gift to his fiancée, Charatza Tragbigzanda. According to Smith's account, Charatza became infatuated with him, and apparently in an attempt to convert Smith to Islam, she sent him to work for her brother, Tymor Bashaw, who ran an agricultural station in present-day Russia, near Rostov. Instead of instructing Smith, Tymore mistreated him by shaving his head, placing an iron ring around his neck, giving him little to eat and often beating him. During one such beating, Smith overpowered Tymore, killing him and fleeing his enslavement using Tymore's horse and clothing. Traveling for days, unsure of his route, Smith was befriended by a Russian and his wife, Callamatta, whom Smith called this "good lady". Their assistance helped Smith regain his strength and begin his travels across the remainder of Russia, Ukraine, Germany, France, Spain, and Morocco before finally returning to England in 1604. One author estimates Smith's travels from 1600-1604 covered nearly 11,000 miles! The captain was finally home, but not for long.

Smith's military exploits impressed prominent men in England, especially Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, a man intent on founding an English colony in the Chesapeake region of Virginia. Gosnold, and other important men in London, organized the Virginia Company of London and were granted a charter by King James I on April 10, 1606, to establish a colony in Virginia. In December 1606, the company dispatched three ships carrying 104 settlers, including Captain John Smith, to start this colony.

Established on May 13, 1607, the colony was named Jamestown, in honor of the king. [It became the first permanent English settlement in North America, and first of 13 English colonies that won independence from England and became the first 13 states of the United States of America.] Jamestown's fate hung in the balance for many years, and some historians credit Jamestown's survival to the efforts of Captain Smith.

Originally, the colony was governed by a council of seven men, and Captain Smith had been named by the Virginia Company to serve on this council. Ironically, he was arrested for mutiny on the voyage to Virginia, narrowly escaping being hanged, and arrived at Jamestown a prisoner. Fortunately, through the efforts of Jamestown's minister, Reverend Robert Hunt, he was allowed to assume his council position.

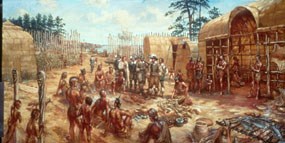

The first months of Jamestown's existence were very difficult due to food shortages, unhealthy drinking water, disease, occasional skirmishing with the Powhatan Indians, and ineffectual council leadership due to bickering and the untimely death of Bartholomew Gosnold. In the fall, Smith conducted expeditions to Powhatan villages securing food for the desperate colonists. On one such expedition in December he was captured by a large Powhatan hunting party and led on a long trek to various Powhatan villages, ultimately being brought before the paramount chief of the Powhatan people, Wahunsenacawh, better known as Chief Powhatan.

This encounter resulted in the famous story written by Smith of being saved from execution by Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan's daughter. [Most historians and anthropologists believe this event occurred, but Smith misinterpreted its meaning not realizing it was a symbolic adoption ceremony of Smith into the world of the Powhatan people.] The captain was released shortly after the ceremony and escorted back to James Fort. By this time, only 38 of the 104 settlers were still alive. More settlers arrived at Jamestown in January 1608, and Chief Powhatan sent some food to the English, but misfortune struck in early January with the accidental burning down of most of the fort. The extreme cold that winter, coupled with the loss of shelter and food from the fire, led to the deaths of more than half of the new settlers.

Smith tried to focus the colonists on their immediate needs and not spend valuable time searching for gold, but he wrote, "There was no talk, no hope, no work but dig gold, wash gold, refine gold, load gold --- such a bruit of GOLD that one mad fellow desired to be buried in the sands, lest they should by their art make gold of his bones!" Despite these fruitless endeavors to find gold, the colony became more stable as additional settlers and food arrived. In the spring of 1608, Captain Smith undertook one of the most important European explorations in North America: the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

On two separate voyages, beginning in June and ending in September 1608, Captain Smith and several of his fellow colonists, traveling in an open barge about 30 feet long and 8 feet wide, explored 2,500 miles of the Chesapeake Bay and many of its tributaries such as the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. From these trips Smith created a very accurate map of the area replete with locations of various Indian villages and other vital information. This exploration and map of the Chesapeake Bay region were some of Captain Smith's greatest accomplishments and enduring legacies.

In September 1608, Smith was elected president of the colony and head of the council. He implemented common sense regulations for the colony such as, "… he that will not work shall not eat…." Under Smith's leadership the death toll dropped dramatically, the fort was repaired, crops planted, a well dug, trees cut into clapboards, and products such as pitch, tar, and soap ash were produced for shipment back to England. Even during times of food shortages, Smith sent colonists to live with the Powhatan Indians confident no harm would befall them as he believed Chief Powhatan and his people feared him and English weapons.

Unfortunately, relations were tenuous between the English and the Powhatan Indians as Smith's diplomacy often turned violent taking food and destroying villages. The final meeting of Captain Smith and Chief Powhatan occurred in January 1609 at Werowocomoco, Powhatan's capital, where each leader plotted the other's death while conducting civil negotiations. Ironically, Chief Powhatan's plan to kill Smith and his colleagues was foiled due to a timely warning given Smith by Pocahontas! Each leader escaped destruction, but Smith's harsh diplomacy heightened the animosity between the two cultures and open warfare soon erupted.

Captain Smith did not witness the First Anglo Powhatan War [1609-1614] or the Starving Time [winter of 1609-1610] having suffered a severe injury from a gunpowder explosion in the fall of 1609 forcing him to return to England. Smith remained interested in Jamestown wanting to return, but Virginia Company officials refused his requests. Always the adventurer, Smith undertook a voyage in 1614 exploring the shores of northern Virginia, which he mapped and re-named New England. Intending to establish an English colony there, Smith's efforts were frustrated when he was captured by French pirates while sailing to New England in 1615. Escaping from the pirates, Smith returned to England where he wrote extensively about his life's adventures. [In 1620, the Pilgrims nearly selected Captain Smith to be their military advisor but instead selected Miles Standish, however, they did use Smith's map of New England.] Captain John Smith died in London on June 21, 1631, and was buried at St. Sepulchre's Church.

John Smith's best biographer, Philip L. Barbour, once wrote, "Captain John Smith has lived on in legend far more thrillingly than even he could have foreseen. Much has been made-largely by ill-informed people-of trivial inconsequences in his narratives, and controversy has at times raged rather absurdly. … To be sure, much of what John Smith wrote was exaggerated. … Rare indeed was the man who wrote in Stuart times without ornament, without exuberance. Let it only be said that nothing John Smith wrote has yet been found to be a lie."

Barbour, Philip. The Three Worlds of Captain John Smith. First. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1964.

Haile (Editor), Edward Wright. Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony, The First Decade: 1607-1617. Second. Champlain, Virginia: Round House, 2001.

Loker, Aleck. The Adventures of John Smith. First. Greensboro, North Carolina: Morgan Reynolds Publishing, 2006.